Linux Package Managers Compared: APT, DNF, Pacman and Zypper

If you’ve hopped between Linux distributions as much as I have, you know that each major family of distros introduces you to a different package manager. At first, it can feel a bit daunting (apt on Debian/Ubuntu, dnf on RHEL/Fedora, pacman on Arch, and zypper on openSUSE), but these tools all serve the same purpose of installing and updating software.

After using Linux for years (across everything from Debian to Arch-based systems), I’ve grown comfortable with all of them. Even niche distros like Slackware, Gentoo, and Void. In this post, I’ll break down the major package managers, how they differ, and what it’s like to use each one. We’ll also touch on the universal package formats (Snap and Flatpak) that aim to work across distributions, and lastly mention a few niche package management systems. Let’s dive in!

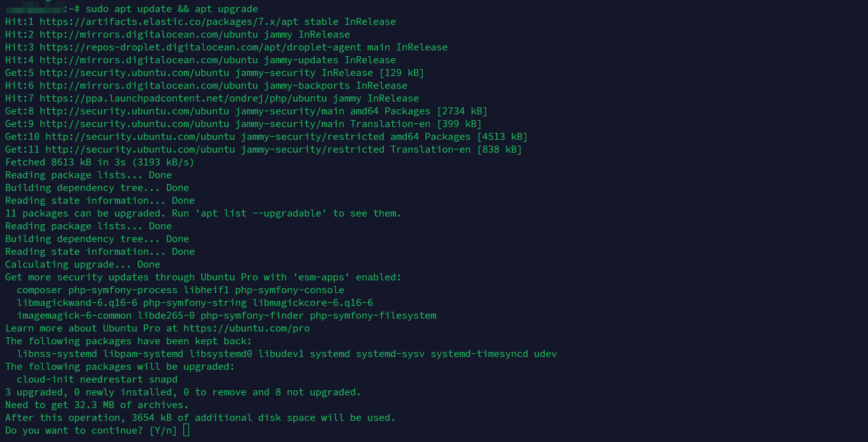

APT (Advanced Package Tool) – Debian/Ubuntu Family

As a long-time Debian and Ubuntu user, APT has been my daily driver for package management. APT is the high-level package manager for Debian and Debian-based distributions (like Ubuntu, Linux Mint, Pop!_OS, etc.), handling software installation, upgrades, and removals.

It works with Debian’s .deb packages (under the hood it uses the lower-level dpkg tool). One thing I appreciate about APT is its vast software repository! Debian’s repos offer tens of thousands of packages (over 60,000), which means most of the software we need is just an apt install away.

Using APT feels straightforward. You typically run sudo apt update to refresh package lists, then sudo apt upgrade (or full-upgrade) to apply updates. Installing is as easy as sudo apt install <package>. The syntax is clear, and APT provides helpful output during operations.

Over the years, APT has evolved (the modern apt command replaced many uses of the classic apt-get for simplicity), but it remains stable and user-friendly. The huge community around APT-based distros means help is always around the corner if something goes wrong.

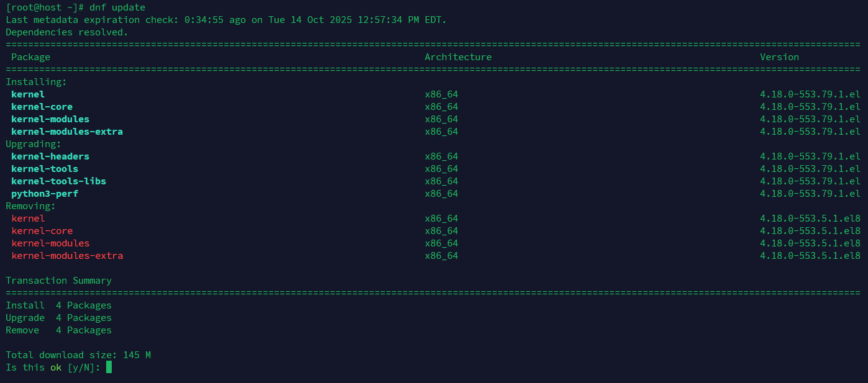

DNF (Dandified YUM) – Red Hat/Fedora Family

Over on the Red Hat side of the world, DNF is the package manager you’ll encounter on Fedora, Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) 8+, AlmaLinux, CentOS Stream, and the like. DNF is essentially “YUM v2.0”. It was introduced as the next-generation replacement for the older yum in Fedora 22 (2015).

In my experience with Fedora servers and workstations, DNF has been a solid tool that improved upon YUM’s shortcomings. It still uses the RPM package format under the hood but offers better performance and dependency management than the old YUM. I remember years ago when YUM could feel a bit slow or get hung up on dependency quirks; DNF has largely solved those issues with a more modern dependency solver (libsolv) and smarter caching.

Using DNF is quite similar in workflow to APT. You’d run sudo dnf upgrade to update packages (or dnf update – both work, though technically “upgrade” is the newer syntax). Installing software is sudo dnf install <package>, and removal is dnf remove <package>.

One thing I like is that DNF automatically refreshes repository metadata as needed (so you don’t always have to manually run a separate “update” command). DNF also has a nice feature where you can view transaction history (dnf history) and even attempt to roll back a transaction if something goes awry.

In practice, I’ve found DNF to be very reliable on my Fedora systems. It’s also scriptable and has plugins for things like automatic upgrades. Overall, DNF gives a sense of an “enterprise-grade” package manager, which is no coincidence since it’s what RHEL uses. Fedora’s short release cycles mean DNF gets a lot of exercise keeping up with frequent updates, and it handles that pace well.

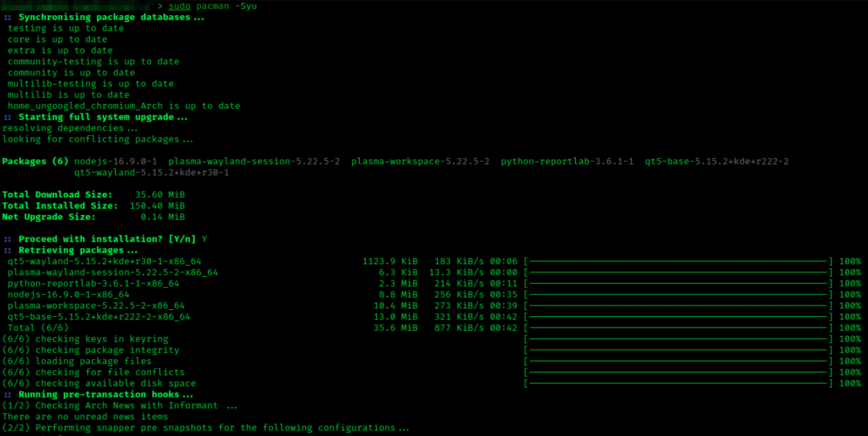

Pacman – Arch Linux Family

Oh boy! I hope I do this justice for those Arch fanatics in our Linux community forums. When I first ventured into Arch Linux, the pacman package manager immediately stood out for its speed and no-nonsense design. Pacman is the default package manager for Arch Linux and Arch-based distros like Manjaro and EndeavourOS. It uses its own simple binary package format (typically .pkg.tar.zst files now) and is known for being lightweight and blisteringly fast!

Many Arch users love that pacman -Syu will synchronize the repos and upgrade the whole system in one go. And it usually does so in a fraction of the time of its counterparts, given a good mirror.

Pacman’s command syntax is a bit different if you’re coming from APT or DNF, but it’s consistent and easy to learn. Packages are installed with pacman -S <package>, removed with pacman -R <package>. Instead of long command names, pacman uses short flags (e.g., -S for sync/install, -Q to query the package database, etc.).

This took me a little time to get used to, but now I really enjoy the efficiency. For example, I can combine operations like pacman -Rns <package> to remove a package and its now-unneeded dependencies in one go. Pacman doesn’t prompt much either; it just does what you ask, which many find refreshing to use.

One of Arch’s strengths is the AUR (Arch User Repository), a massive collection of community-contributed build scripts for software not in the official repos. Pacman itself doesn’t directly manage AUR packages (you use helper tools for that, like yay and paru), but it’s part of the Arch package ecosystem and contributes to why Arch/pacman users have access to virtually any software. If I need some niche program, chances are an AUR script exists and pacman can install the resulting package.

The trade-off with pacman’s minimalist approach is that it places more responsibility on the user: for example, you should do full system upgrades (partial upgrades risk breaking dependencies) and read Arch’s news for any manual interventions needed. But as long as you keep your system updated, Arch’s repositories are well-curated and pacman’s dependency solver is straightforward. In short, pacman exemplifies Arch’s philosophy: simple, transparent, and fast!

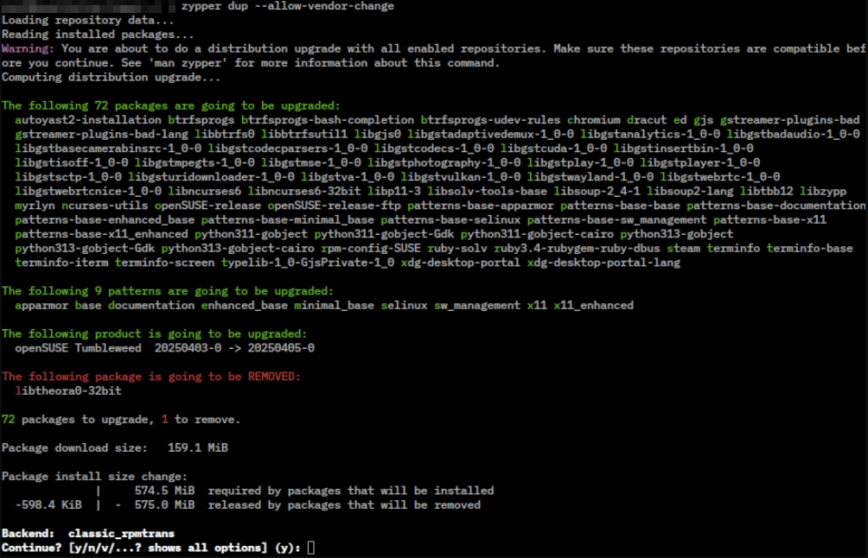

Zypper – openSUSE/SUSE Family

During a period when I ran openSUSE Tumbleweed on a machine, I got familiar with Zypper, the package manager for SUSE-based distros. Zypper is not as talked about in mainstream Linux discussions, but it deserves a lot of credit. It manages .rpm packages for openSUSE Leap/Tumbleweed and SUSE Linux Enterprise (SLE), powered by the robust libzypp backend.

In use, Zypper feels a bit like a hybrid of apt and dnf in terms of syntax and capabilities. You refresh repositories with sudo zypper refresh, upgrade with sudo zypper update (or zypper dup for a distro upgrade or Tumbleweed full update), and install packages with sudo zypper install <package>. The commands are intuitive, and zypper outputs clear, colored info when it’s resolving dependencies or suggesting additional changes.

One area where Zypper shines is dependency resolution and system management. I’ve found Zypper to be very smart about picking solutions if there’s a package conflict. It will often present me with a few options (“do you want to downgrade package X to solve this dependency, or switch vendor, etc.”) in a way apt or pacman typically don’t. It also supports vendor sticking, patterns (group installations of related software, like a LAMP stack pattern), and can even roll back system changes when used with Btrfs snapshots (openSUSE’s default filesystem uses Snapper to snapshot before updates).

In fact, with openSUSE’s default setup, if an update goes wrong, you can reboot and select a prior snapshot, a safety net that apt and pacman lack natively. That gave me a lot of confidence when running rolling-release Tumbleweed; I knew Zypper plus Snapper had my back.

Performance-wise, Zypper is quite reasonable. It might not feel as lightning-fast as pacman, but it’s not sluggish either. The slight overhead comes with the benefit of comprehensive checks. I also like that Zypper can auto-refresh repos at set intervals and has a clean output when searching (zypper search <name> to find packages).

The community around openSUSE is smaller, so there are fewer “Zypper vs. others” debates out there, but in my personal use I found nothing to complain about. It’s a reliable, enterprise-capable package manager. Whether running the stable Leap release or the bleeding-edge Tumbleweed, Zypper works without drama.

Edit: Also see my remarks about OBS here.

Comparison Tables: APT vs DNF vs Pacman vs Zypper

| Package Manager | Speed | Dependency Resolution | System Management | Ecosystem Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APT | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| DNF | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 (5 w/ Flatpak) |

| Pacman | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 (5 w/ AUR) |

| Zypper | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 (5 w/ OBS) |

All of these package managers are command-line based by default, but most have GUI frontends available: e.g., Gnome Software Center for APT and DNF, Octopi/Pamac for Pacman, and YaST Software Manager for Zypper.

Here’s how I would personally summarize some key characteristics of these four amazing package managers (so you can better understand my ranking):

| Package Manager | Primary Distros | Package Format | Notable Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| APT | Debian, Ubuntu, Linux Mint, etc. | .deb (dpkg backend) | Largest software repositories, most third-party apps support .deb; user-friendly commands (apt install/update); strong stability, and dependency handling by default. |

| DNF | Fedora, RHEL (8+), CentOS Stream, AlmaLinux, etc. | .rpm (RPM Package Manager backend) | Modern YUM replacement with improved speed and memory usage; automatic metadata refresh; supports rich dependency solving and rollback via history; plugin ecosystem for extensibility. |

| Pacman | Arch Linux, Manjaro, EndeavourOS, etc. | .pkg.tar.zst (tarball packages with simple compression) | Extremely fast and efficient! Simple one-command sync & upgrade (pacman -Syu); no separate update vs. upgrade steps; complemented by the AUR for huge community-driven package selection. Requires frequent full updates (rolling release philosophy). |

| Zypper | openSUSE (Tumbleweed/Leap), SUSE Linux Enterprise | .rpm (RPM with libzypp) | Robust dependency resolver with advanced features; can handle distro upgrades and pattern installs; integrates with Btrfs for snapshot rollbacks (on openSUSE); slightly less mainstream but enterprise-proven reliability. |

As discussed, each tool has its own syntax and philosophy, yet they share the same goal: keeping your system’s software up-to-date and consistent. When I switch between distros, it usually only takes a few minutes to adjust my muscle memory to the new package manager.

For example, after using apt for so long, typing dnf felt strange at first, or remembering to use -S instead of install with pacman. But underneath the commands, the concepts (update the database, install packages, resolve dependencies, etc.) are very much alike. As such, I removed the ease-of-use column from my above rankings table because it’s subjective and the difference is slim since all are fairly easy to use.

Universal Package Formats: Snap and Flatpak

Modern Linux distributions often support additional universal packaging formats like Snap and Flatpak, which provide sandboxed, cross-distro applications. AppImage also exists as a portable binary format, though it’s less widely adopted today. The idea is to package an application along with (most of) its dependencies in a format that any distro can run, independent of the native package manager.

Snap

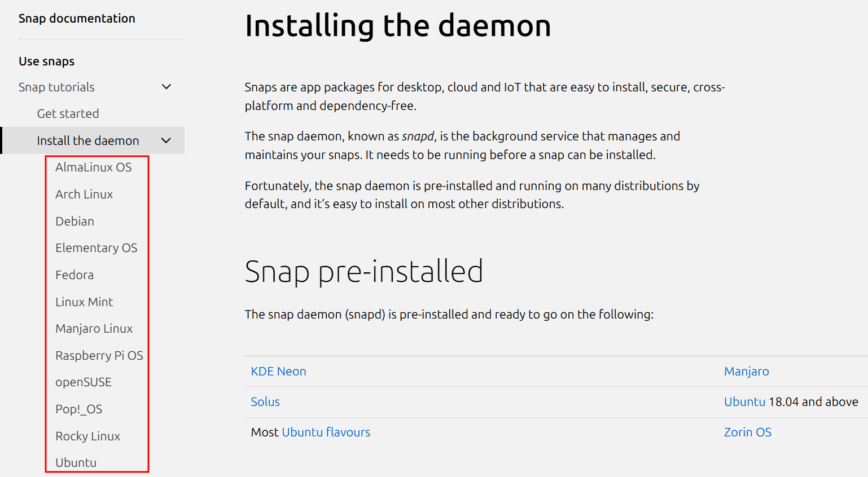

Ubuntu’s parent company, Canonical, introduced Snap as a way to deliver software in a container-like format. Snaps are mounted at runtime and isolated from the core system. Snaps auto-update in the background and work the same across any distro that has the snapd service running.

The downside is they can be a bit heavy. A Snap package includes all its necessary libraries, which can make it large, and the first launch can be slow (as it sets up the sandbox). Also, Snap’s centralized nature (Snap Store controlled by Canonical) and the automatic updates have been points of contention for some users.

Still, Snap fulfills the “works on any distro” promise, providing an easy way to get software regardless of whether you’re on Ubuntu, Fedora, or Arch. Saving time and complexity.

Flatpak

This is a similar concept but originated in the Fedora/Red Hat community and is governed more openly (via the Freedesktop project). Flatpak focuses on desktop apps and sandboxing for security.

In my experience, Flatpak is great for getting applications on any distro with strong isolation (each app runs in its own container with only the permissions you grant). Flatpaks typically come from Flathub, a central repository, though one can add other repos or even self-host. I’ve used Flatpak on openSUSE and Debian to install apps like Spotify and VS Code in their latest versions, without tainting the base system.

Flatpak and Snap are similar in goals (bundle dependencies, run anywhere), but Flatpak feels more community-driven. One notable difference: Flatpak doesn’t enforce automatic updates; you update Flatpak apps via flatpak commands or a software center when you choose. Flatpak also shares runtime libraries between apps when possible, to save space.

My Take on Universal Packaging in Linux

On the whole, both Flatpak and Snap solve the “it works on my distro” problem. For example, Flatpak apps run independently of the host OS’s libraries, avoiding the dreaded “dependency hell” across different distros. The trade-off is they use more disk space and memory than a native package, and integration (theme, file dialogs) can sometimes be a bit off.

In my personal workflow, I still tend to use the distro’s package manager for the vast majority of things, but I’m increasingly seeing the value of these tools in specific use cases. For instance, on an immutable distro (where the base system is read-only), Flatpak or Snap are often required for adding new applications.

I’ll admit I was late to the Flatpak party, focusing mostly on traditional packages. But nowadays, I’m glad to have these options. They make Linux software distribution more accessible, and you can target “Linux” as a whole without packaging separately for each distro. It’s not a perfect silver bullet (there’s some duplication of effort and resources), but it’s a big step toward a more unified Linux desktop experience.

Other Niche Package Managers

Linux being Linux, there are many package management systems beyond the big four! Depending on the distros or ecosystems you explore, you might encounter some of these niche or specialized package managers:

Portage (Gentoo Linux)

Gentoo doesn’t use pre-compiled binary packages by default. Instead, it uses Portage and the emerge command to compile everything from source. This is a completely different philosophy. When I ran a Gentoo system, it was both challenging and rewarding: you have immense control over build options and optimizations, but installing large applications can take a ton of time due to compilation.

Portage uses “ebuild” scripts and a rolling release model like Arch. It’s highly customizable and flexible, aimed at power users who want to tune their system to the fullest. The upside is you get exactly what you configure (and you learn a ton in the process); the downside is the time and effort: it’s not as plug-and-play as APT, DNF, etc.

Gentoo’s Portage is essentially the extreme opposite of something like Ubuntu’s Snap: Portage gives you maximum control and compiles on your machine, whereas Snap gives you a pre-made binary in a container. I have deep respect for Portage (it taught me a lot about dependencies), but these days I don’t have the patience. Still, Gentoo fans swear by the optimization and bloat-free result of a well-tuned Portage system!

Pacman Alternatives on Arch

On Arch Linux, pacman itself is king, but as I briefly mentioned above, there are helper tools like yay, paru, and others that extend pacman to easily build/install AUR packages. These aren’t separate package managers per se (they ultimately call pacman and/or makepkg under the hood), but they simplify using the Arch User Repository.

I’ve used yay on my Arch systems to grab AUR packages with a single command (it handles fetching the PKGBUILD, building it, and installing via pacman). There’s also the older tool Yaourt (now deprecated), which I used a lot, and others. While these wrap pacman, the fact that the community creates such tools highlights Arch’s DIY spirit.

Nix (NixOS) and GNU Guix

These are fascinating takes on package management that are functional and declarative. I’ve only experimented lightly with Nix, but it approaches the system as a set of build definitions. You can install Nix on many distributions (not just NixOS) and use the nix-env command to install software in a way that is fully isolated from your main system. Nix and Guix allow atomic upgrades and rollbacks. If something goes wrong, you can roll back to a previous generation of your environment.

They also support having multiple versions of a package coexist. Guix is very similar to Nix (Guix builds on GNU’s principles and only includes free software by default). The learning curve for Nix/Guix is quite steep, I felt like a newcomer since they are unlike the traditional managers. You write declarative configurations and let the system “realize” that state. It’s incredibly powerful (e.g., you can set up an entire development environment with specific compiler versions and libraries without messing up your base system), but it bends your mind a bit if you come from the apt/yum world.

I think of Nix/Guix as not just package managers but as package+configuration management systems. They’re popular among folks who value reproducibility. For example, DevOps and HPC people who need to ensure an environment can be recreated exactly.

Personally, I haven’t switched to using Nix or Guix as my daily package manager, but I see the appeal. In fact, some newer distros like Vanilla OS are experimenting with using a mix of technologies. Even using (apx) that can tap into apt, dnf, pacman, or apk (Alpine’s manager) in containers, along with supporting Flatpak and letting you use the system immutably. It’s a bit wild, an indicator that we might even see combinations of package managers to leverage each of their strengths.

Also read: Immutable Linux Distros: Are They Right for You? Take the Test.

Others

There are more worth mentioning briefly: APK is Alpine Linux’s tiny package manager (designed for efficiency in container environments), Slackware has its traditional tarball packages managed with tools like installpkg/removepkg (with no automatic dependency resolution), and pkg (not to be confused with pacman’s .pkg files) is the package manager on FreeBSD (not Linux, but if you ever venture into BSD).

There’s also Homebrew (well, Linuxbrew), which isn’t a system package manager but is popular for installing userland apps on any distro by compiling from source (I use brew for some tools on Ubuntu; it works independently of apt). Each of these caters to specific niches or philosophies. For example, Alpine’s APK keeps things minimal for containers, and Slackware’s approach assumes the user will manually handle any library needs (which some people actually prefer for its transparency).

The key takeaway is that package management is a rich field, and there’s no one-size-fits-all! Each approach has trade-offs between convenience, control, security, and simplicity/time.

Conclusion

Having used all these package managers, I’ve come to realize there isn’t a single “best” package manager. It really depends on your needs and which distribution you’re running. APT, DNF, Pacman, Zypper all excel in the environments they were designed for. These days I split my time between a Debian/Ubuntu-based distro (for its stability and APT familiarity) and a rolling-release distro (currently Kali Linux’s rolling branch, which uses APT as well, and occasionally Arch in a VM for fun). Each time I switch context, muscle memory kicks in, and I’m typing the right commands in short order.

For new Linux users, APT and DNF tend to be very approachable, with lots of documentation and community support. Pacman might feel terse at first, but it’s equally reliable once you learn it, and Arch’s wiki has excellent docs. Zypper is perhaps underappreciated, but anyone who tries openSUSE will find it straightforward and powerful.

In the end, package managers are just a means to an end: getting the software you need, when you need it, and keeping your system healthy. Whether I’m running sudo apt upgrade or sudo pacman -Syu, I know I’m invoking the same Linux tradition of software management that’s been honed for decades. And if something isn’t available in one of them, well, that’s when I turn to a Flatpak or AppImage as a quick solution.

Personally, I love the speed of pacman and the huge repositories of APT. DNF has grown on me for its polish in Fedora, and Zypper’s robustness in openSUSE is confidence-inspiring. It’s almost like choosing a favorite tool out of a toolbox; you pick the one that fits the task. Luckily, with Linux, we have access to the whole toolbox!

Continue reading:

- Linux Commands Frequently Used by Linux Sysadmins – Part 1

- Immutable Linux Distros: Are They Right for You? Take the Test.

- Should I stay on Arch or try Fedora?

- 9 Most Stable Linux “Rolling Release” Distributions.

Eopkg didn’t even get a mention in niche. Solus does really = alone. That said, good write-up.

You are right! I thought I got most. Definitely deserved a mention. Thanks for adding that.

Definitely deserved a mention. Thanks for adding that.

@hydn Once again you have done some excellent work. My overall comment is that when I began with Linux, in my opinion the only package managers worth anything were apt-get, simple Slackware packaging, and the early Mandrake tools with the .rpm package format. Since then there has been incredible progress. Though zypper seemed perhaps less impressive to you, I think it’s probably the most improved of all the different packaging front end tools. SUSE has long been an outstanding distribution, but until zypper came out, package management was arguably their weakest point. To me using zypper now is effortless. When I have an openSUSE setup I typically alias the zypper dup command and away I go; very easy for a tool that does so much.

The other infrastructure that’s come at least as far, maybe more so are the Arch Linux derivatives. It was once assumed that the only people who could use Arch were the people willing to dig through the system and build or install whatever they wanted. Okay, powerful, but distributions now realize that most people don’t want to waste their time that way, and if they do, they’ll build what they want from scratch. Pacman has done a lot, but yay has really simplified the game. Both Endeavour OS and Cachy OS now have welcome screens that will even call those tools FOR you! It’s about time there were conveniences like that. I didn’t even have to build a bunch of alias commands to call up my tools there either.

Fedora was also a mess, but they fixed up their stuff a long time ago, but the only thing that gets me is that they keep changing the front end to their package managers. Get it right and stick with it guys!

In any case, overall package handling and management has made tremendous strides in the past 25-30 years and I’m grateful.

Nice article and explanation of several of the most common package managers!

I really appreciate the thoughtful feedback and I completely agree with you on Zypper. In fact, it’s the only package manager in my comparison that got a full 5 in both system management and dependency resolution. It’s come a long way, and I’ve also found it to be one of the most seamless to use once it’s set up.

Your point on Arch and tools like yay is spot on. Pacman’s always been fast, but the AUR ecosystem plus helper tools really changed how approachable Arch-based distros are. Endeavour and Cachy in particular have lowered the barrier without losing the flexibility Arch users value.

And yes, Fedora has matured a lot too, even if they’ve switched frontends a few times. But so has Ubuntu and Debian.

But so has Ubuntu and Debian.

All in all, I share your view: Linux package management has evolved massively since the early apt-get and Slackware days. It’s impressive how much polish and choice users have now.

Well written article

next benchmark apk vs pacman fair enough.

Last used apt back in 2022 debian were apt is much slower i give it 1 or 2 rate

dunno if modern version got faster but nice we get these results