Raspberry Pi Reliability Has a Storage Problem

Raspberry Pi board has earned its reputation as one of the most versatile and capable single-board computers ever made. From home labs, to kiosks and lightweight infrastructure, the hardware itself is rarely the limiting factor. When things go wrong, it’s usually not CPU, memory, or thermals. It’s something much more basic: storage.

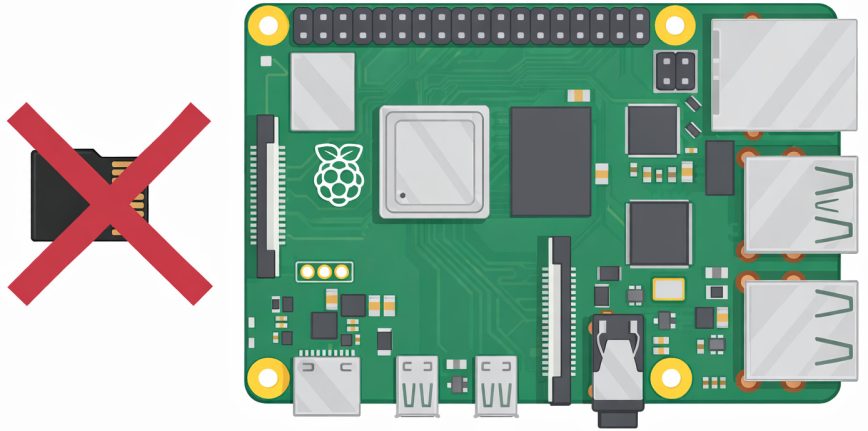

Over years of real-world use, SD and microSD cards have consistently proven to be the most fragile and failure-prone part of otherwise solid Raspberry Pi setups. At some point, that stops feeling like bad luck and starts raising a bigger question. Is the platform being held back by a storage choice that no longer makes sense?

microSD Has Always Been the Weak Link

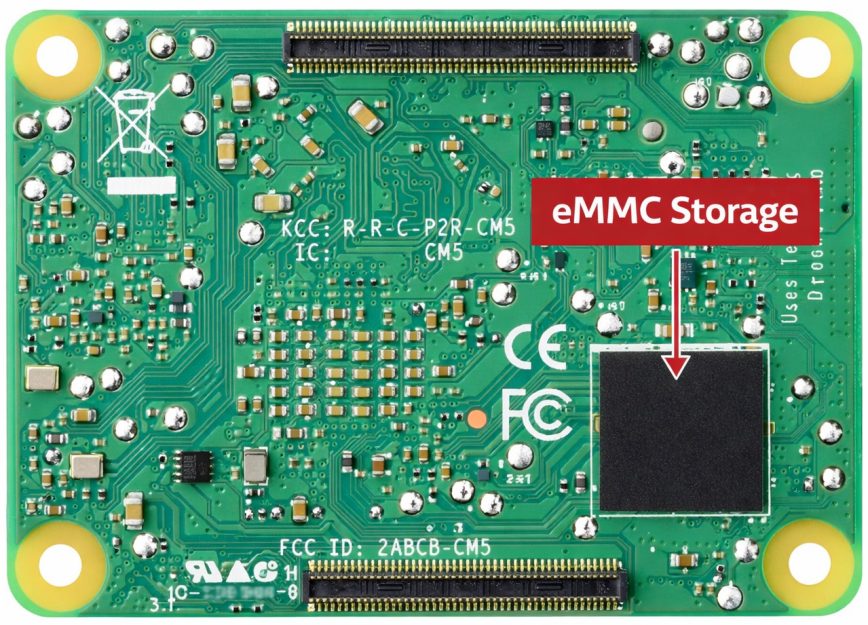

To be fair, Raspberry Pi already knows this. The Compute Module line uses onboard eMMC flash, and that’s not an accident. eMMC is generally more reliable than typical microSD cards because it uses higher-quality NAND, includes proper wear leveling handled by the controller, and removes a lot of the randomness that comes with consumer removable media. The fact that eMMC exists in the Raspberry Pi ecosystem at all shows that reliability has already been acknowledged as a concern.

On the mainstream Raspberry Pi boards, SD and microSD remain the weakest link. Boot failures, random corruption, and systems that suddenly freeze are not rare edge cases. They happen often. Especially in setups that run unattended or experience the occasional power loss. And yes, this is even when the correct power supply is used!

Raspberry Pi has no control over the quality, firmware behavior, or endurance of the microSD cards people use. Even when buying reputable brands, reliability is all over the place. I’ve experienced this firsthand with high-end cards from major manufacturers. One model will run perfectly for years. Another card from the same brand, will corrupt repeatedly under similar conditions. Same brand. Different model numbers. Entirely different outcomes.

Raspberry Pi boards themselves are incredibly reliable largely because they’re made up of soldered components. Soldered eMMC follows that same philosophy. It’s predictable, controlled, and far less prone to random failure.

Power loss makes everything worse. MicroSD cards are especially vulnerable during writes, and their slow write speeds combined with limited power-loss protection make filesystem corruption far more likely. In one recent case, a Raspberry Pi was running as a Unifi Controller for a friend’s home Wi-Fi setup. After a power interruption, the Pi rebooted and never came back up. The board itself was fine. The microSD card was corrupted and unbootable. The hardware didn’t fail. The storage did.

I wrote about that experience in the article, Raspberry Pi Not Booting: How to Repair Micro SD Card.

Why Raspberry Pi Should Move Beyond microSD

Raspberry Pi Compute Module 5 (CM5) already uses onboard eMMC.

For future boards like the upcoming Raspberry Pi 6, a more reliable design would be to include a small amount of onboard eMMC for the base system, even something modest like 16 or 32 GB, paired with a short-form NVMe slot for expansion. Alternatively, just replacing MicroSD with M.2 NVMe support only.

While writing this post, I searched online to see if the Raspberry Pi 6 was already in the works. What I found was this outstanding forum post that was immediately locked by Raspberry Pi forum moderators. So this must be a very sensitive topic among those in the Raspberry Pi community.

The irony is that the Raspberry Pi boards themselves are incredibly reliable largely because they’re made up of soldered components. Soldered eMMC follows that same philosophy. It’s predictable, controlled, and far less prone to random failure.

Short-Form NVMe Makes Sense on a Raspberry Pi

To be clear, this doesn’t mean full-length consumer SSDs. Standard M.2 2280 NVMe drives are simply too long to fit on a Raspberry Pi-sized board. What makes sense here are the shorter NVMe form factors that already exist and are widely used, specifically M.2 2230 and M.2 2242. These drives are compact enough to mount directly on small boards while still offering vastly better performance and endurance than microSD cards.

eMMC brings clear advantages as a base layer. It’s soldered, standardized, and behaves consistently. Raspberry Pi 6 could use this single eMMC configuration and guarantee a known and proven baseline of storage reliability. That alone would eliminate a large class of boot failures and corruption issues.

Yes, users would still be choosing their own NVMe drives, but NVMe devices are generally built with better controllers, higher endurance, and stronger error handling than microSD cards. The failure characteristics simply aren’t comparable.

NVMe operates in an entirely different reliability tier compared to microSD. In my own setups, even inexpensive, off-brand NVMe drives like the 256 GB TEAMGROUP MP33 that I purchased back in 2022 have proven dramatically more resilient than microSDs. I’ve been running low-cost NVMe drives for years across multiple devices, and they’ve survived repeated sudden power losses without corruption or failure.

The above NVMe requires a Raspberry Pi 5-compatible M.2 adapter HAT.

Cost is the obvious concern, and this is where Raspberry Pi could still keep things accessible. A small onboard eMMC doesn’t need to replace expandable storage entirely. It only needs to provide a reliable boot and base OS layer. Users who want more space or higher performance could add a short-form NVMe drive. Users who want the lowest-cost option could rely solely on the onboard eMMC storage. That kind of hybrid approach would significantly improve reliability without turning the platform into a high-end SBC.

In Closing

As things stand, microSD cards introduce a reliability lottery that undermines what is otherwise excellent hardware. For hobby projects, home infrastructure, kiosks, controllers, or anything expected to run continuously, it’s an annoyance. And that’s really the core issue. The Pi itself is rarely the problem. The storage is. What has been your experience with the Raspberry Pi 1 through 5 and reliability?

Continue reading:

- What to buy for your Raspberry Pi 4

- What to buy for your Raspberry Pi 5

- Learn Linux: 4 Devices to Boost Your Linux Skills (2026)

Agreed. Pure and simple. One of these days, if I have the time, maybe I play around with one. I probably need memory prices to come down a tad first.

I’ve had a raspberry pi from each generation. They helped me learn and hone the skills that I have today and I’ve loved having them on the network. I currently run two Raspberry Pi 5 8GB models as active participants on my network (PiHole/Icinga2/Nagios/other monitoring services and my bastion/jumpbox) and they run great.

I did have a Pi 4 acting as my PiHole/Icinga2/Nagios box for at least a year, maybe more. The only reason I’m not running it now is b/c I got the 2nd Pi 5 as a gift, so figured why not take the boost to hardware specs. The only Pi 4 I have running currently is used for a camera setup to keep an eye on my older cat when we take vacations and it’s currently running Raspbian Lite as well, which I believe is on Debian 12 right now (though I did install this one, it did not get an upgrade in place).

I can’t say I’ve had any update/upgrade problems with any Pi, but I do primarily run the Raspbian Lite OS. I’ve not tried to run any other OSes on them, so I can’t speak to them in that regard. I’m always open to new projects on them, if you really don’t have a use for them, I can find a home for them pretty easily here!

How far do you live from me? I need to check out shipping rates.

The main issue I’ve had with RPi boards isn’t with the boards themselves as @J_J_Sloan also indicated (OS issues). But in my case it’s repeatedly the SD and now microSD cards.

I really wish they would abandon that route and launch with eMMC on board (like the Compute Module boards) with a short m.2 nvme slot replacing microSD.

RPi boards feel a bit stagnant and deaf to feedback these days. We can’t dismiss the massive impact they’ve had on education, hobbyists, and low-cost computing worldwide, but that doesn’t mean they should stop evolving where real-world reliability is concerned.

Mi impression for first version of RPi B and RPi 2 B+ was good.

Once I became familiar with the hardware and the philosophy of handling data trees and control through overlays, I detected two problems: the fragility of the SD card in the face of power failures, and the slow speed of this device type.

As a result, I focused the applications on running in memory, I arranged an alternative buffer power supply system with a signal for a controlled shutdown of all systems, and sufficient power autonomy time for it to be completed.

Simultaneously, I installed an adapter for each of the SDIO bus systems where the SD card and eMMC memory were connected. Initially, I started using a secondary, high-quality storage via SPI.

However, SPI was slow and power-intensive; the four signals—MISO (Master In Slave Out, sends data), MOSI (Master Out Slave In, receives data), SCK (Serial Clock receiver to tx sync), and CS (Chip Select from SPI Bus)—did not provide the necessary data transfer speed.

I had to deal not only with the adaptation to 3.3V, but also with the 1.8V adaptation, which allowed me, after modifying the kernel, the boot overlays, and other elements, to use the other four SDIO lines that allowed it to work faster and at a much higher speed, with UHS units instead of DS/HS, through said SDIO communication interface.

You can configure SDIO Clock(25Mhz-208Mhz) to media at GPIOs 22(CLK),23(CMD),24(DAT0),25(DAT1),26(DAT2),27(DAT3), on SD host/eMMC or pinout. Token commands are 48 bit on SPI mode, one bit(DS/HS,3.3V) or four bits(UHS, 1,8V) data lines.

The result was acceptable, for the stack of RPi units, their connections to physical and logical applications, but as @J_J_Sloan points out, it’s pretty, and going through that effort again when they switched to a superior architecture, with a different ABI, wasn’t convenient to continue, and I didn’t use the new RPi versions, except for the RPi Zero, which carries the BCM from my development version.

RPi’s went through those systems: RTOS, Alpine, Debian, BSD derivatives, and many others, even some university practice OSs (ZeOS) for computer science students.

Now they’re just a memory, stored away, that should still work. It was great learning so much, dedicating countless hours to that hobby. They sit next to the Stellaris Launchpad LM4F120, Beagle Bone Black, Beagle Bone, Arduino Uno, Arduino Mega, Atmel ATTYNY44A and 817-XMINI, Onion Omega, Onion Omega2, Nvidia Jetson TX2, Jetson Nano, and other development systems and devices I’m currently testing.

But everything has its time and place. I appreciate what it have given me, and I continue to move forward, because otherwise I would still be writing code in FORTRAN and COBOL on the DIGITAL PDP-11, or on the VAX8200, and then in BASIC with my Sinclair ZX81, and then Spectrum, or MSX, before the 8086 architecture with MS-DOS arrived at my country, Catalonia.

As they say, it was nice while it lasted, but that’s water under the bridge now. These were learning experiences for every situation. Time was passed XD